Are perch the new wrasse?

December 23, 2016

By Tom Walker

The use of cleaner fish as biological controls to reduce sea lice infestations reduces the need for chemical treatments resulting in an economic benefit to farmers and improved health and welfare of salmon

The use of cleaner fish as biological controls to reduce sea lice infestations reduces the need for chemical treatments resulting in an economic benefit to farmers and improved health and welfare of salmonResearch on using Pacific perch as cleaner fish to remove sea lice from farmed Atlantic salmon in British Columbia is moving faster than expected and showing positive results.

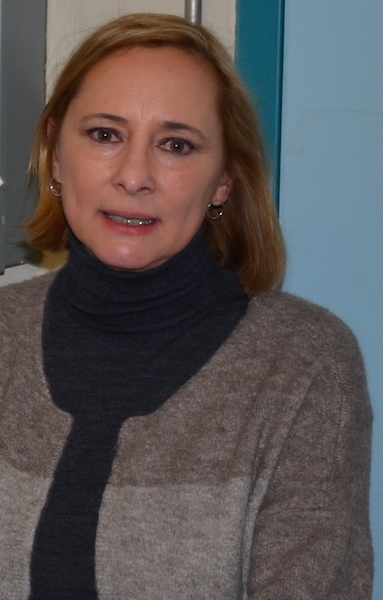

“We expected our first trial to last two to three months,” says Dr Shannon Balfry, who leads

ateam investigating the use of local perch as cleaner fish, a project organized through the Vancouver Aquarium. “When we checked back after five days, the sea lice were all gone and so was the evidence [that they were ever there],” she chuckles. Current trials are only 48 hours.

“We now have so much evidence that the perch eat the sea lice,” says Balfry. “We find the lice in their stomachs and we have video of the perch picking lice off the salmon.” Indeed they have stopped doing post mortems on the perch and now simply collect and count exoskeletons in the perch feces, in order to conserve their stock of perch.

Balfry conveyed her enthusiasm for the project while giving Aquaculture North America (ANA) a tour at the Fisheries and Oceans Canada Center for Aquatic and Environmental Research in West Vancouver, where the project is based.

“The ability to use cleaner fish as biological controls to reduce sea lice infestations in farmed Atlantic salmon would have such a widespread positive impact on the industry,” Balfry notes. Fewer chemical treatments would be of economic benefit to farmers. The health and welfare of salmon would improve for better growth performance and the environment would benefit from fewer chemicals being used.

In BC, environmental organizations express concern over the potential for the spread of sea lice from farmed salmon to wild salmon. “The use of cleaner fish to reduce sea lice infestations is an environmentally friendly solution to this issue of protecting wild salmon populations,” says Balfry.

First-of-a-kind research

This research is the first of its kind on the west coast. “Marine Harvest (BC) phoned and asked if I knew about salmon farmers in Norway using lumpfish and wrasse as cleaner fish in their net pens,” Balfry recalls. “We don’t have wrasse or lumpfish in BC, but when I went back through the literature I found several reports from the 70s, of researchers observing cleaning behavior in local kelp perch (Brachyistius frenatus) and pile perch (Rhacochilus vacca).”

The initial research was funded by the grants Balfry received through the Vancouver Aquarium Marine Science Center. Additional funds came from the BC Salmon Farmers Association and their Marine Environmental Research program, and SeaPact, a group comprised of North American seafood companies.

Marine Harvest Canada has supplied juvenile salmon and sea lice egg strings. The perch are available through the Vancouver Aquarium’s collection program.

There are a lot of factors to this research. “It’s a challenge,” says Balfry. “Sea lice had to be hatched and raised successfully and we had help from Dr Simon Jones at Fisheries and Oceans Canada to learn their culture.” The juvenile salmon they use as hosts must be kept healthy and then infected at the right time. The perch must also be kept and fed.

Balfry says it does not seem to matter that the salmon are a non-indigenous species. “The perch are just interested in the lice,” she points out. “When we first put an infected salmon in with a perch, the perch would immediately start to circle the salmon to check it out.”

The perch are quite shy Balfry says, adding that they construct artificial kelp-like “hides” in tanks for the perch to take cover. When the staff turns off the lights and leave, the perch move in to feed. “We have video taken on our underwater Go Pro cameras that show the salmon tilting to one side so the perch can better access the lice.”

Because the perch are such active feeders, Balfry says they have been able to do multiple trials within a short time. They have tried various perch-to-salmon stocking densities, smaller and larger perch (the smaller fish are more active feeders) and hungry and well-fed perch (it doesn’t seem to matter). Cleaning behavior can be inconsistent – one perch might not be interested one particular day, but will take lice in a subsequent trial.

Further studies

Balfry says her next work will be in deployment research to determine the optimal stocking ratio of perch to salmon and how to scale up the culture of perch. “A perch breeding program and hatchery will be needed to stock the net pens, so there is lots of work to do with the perch,” says Belfry, adding that there is much to learn about perch physiology, health and nutrition.

“One good thing is that the perch are born alive so we won’t have to develop any hatching protocols,” says Balfry. “They have bred on their own here in captivity, but we will need to know how to feed them when sea lice are not at a target size and also ensure that they don’t develop a taste for salmon feed in preference to lice.” Any disease issues for the perch must also be fully understood.

The use of cleaner fish in net pens is now routine in Norway and Scotland and the production of cleaner fish is a major support industry to salmon farming companies. Balfry says she visited a lumpfish culture facility in Norway earlier this year. “If you have 100,000 salmon in a pen with a 10-percent stocking ratio of perch, we are going to need a lot of perch.”

The team is currently developing the logistics around field trials and expect to start cage studies in 2018.

“The industry has been incredibly supportive of this research,” says Balfry.

— Tom Walker