Dulse: the next big wave in aquaculture?

October 28, 2016

By Heather Wiedenhoft

The seaweed has twice the nutritional value of kale and tastes like bacon.

The seaweed has twice the nutritional value of kale and tastes like bacon.

What is more productive than rice and wheat, more nutritious than salmon, tastes like bacon when fried, and was once used as a source of food for abalone? It is Palmaria mollis, better known as dulse, which the Oregon State University’s (OSU) Food Innovation Center is hoping will be the next big wave in aquaculture.

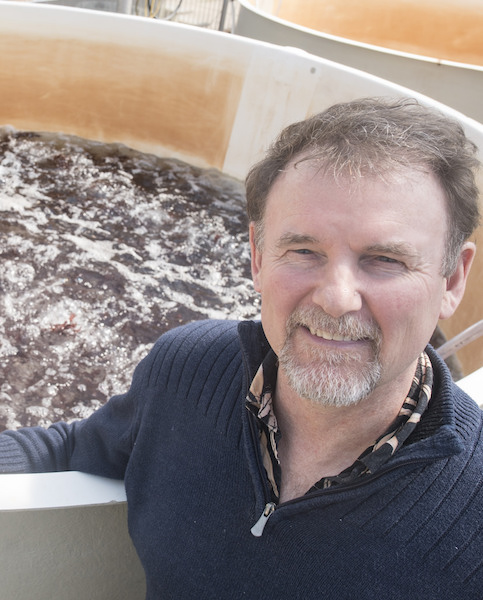

Chris Langdon, a Professor of Fisheries at OSU, started growing dulse in the 1980s as atreatment for effluents from land-based salmon aquaculture. He later found a use for dulse as a food source for an abalone polyculture study. With dulse, the abalone “had both a home and built-in buffet,” explains Langdon, since the larvae could settle right on the plant to live and feed. He saw their growth skyrocket by up to 18 percent a day.

Over the years Langdon produced and patented his own strain of non-reproductive dulse, Palmaria mollis, which grow in tumble-cultured vats kept bubbling with fresh seawater. He shared his fast-growing seaweed strain with NOAA’s aquaculture facility in Manchester, Washington, for further research studies.

Marketing dulse

But the real interest that pushed the seaweed onto the national stage came from an unlikely source: a professor from OSU’s school of business, Chuck Toombs. Toombs was looking for a new product for his marketing students, and was inspired by the nutritional resume of dulse. High in vitamins, antioxidants and minerals, it is up to 16 percent protein and contains taurine, an organic compound not found in soy and missing from most vegan diets. Dulse also has twice the nutritional value of the current darling of veggie lovers, kale.

Add to that the high productivity of cultured dulse, which grows 5 to 8 percent per day, yielding a harvestable product every two weeks. Unlike dulse collected from the wild, the OSU dulse can be produced year-round, has a consistent quality, and harvesting it has no impact on the environment.

Toombs shopped his idea to market dulse to the product and process development team of OSU’s Food and Innovation Center to see what they could come up with. The team in turn enlisted the help of local chefs to try the product out in culinary experiments.

The idea of people consuming seaweed is not new; there are records of Celtic monks in Scotland harvesting the salty snack from rocky shores dating back to AD563 and Asian cultures have long used a wide variety of macroalgae in their diets. But the briny, slimy, sometimes bumpy, wrinkled and rough textured plant has been a harder sell for American palates. The Food Innovation Center had some early success with dulse marketed in the form of salad dressing or juice smoothies by Odwalla, sold at New Seasons grocery stores.

Embracing the challenge, one James Beard nominated chef in Portland took a more direct approach, deep-frying the frilly purplish vegetable until crispy, then garnishing salads with it. What came out of this experiment was unexpected: a deep umami flavor reminiscent of what is arguably everyone’s favorite pork product — bacon. Suddenly, the phrase “Tastes like bacon!” had caught fire on social media and was broadcast nationally on CBS and NBC News.

With all the positive attention finally being lavished on this salty superfood, the Food and Innovation Center applied for and received “specialty crop” status and grant funding from Oregon’s Department of Agriculture. The status represents a milestone for algae aquaculture since seafood had never been labeled as a “specialty crop” by the department before.

OSU plans to use the additional funding to further integrate dulse into foods, cosmetics, and possibly, even biofuels. “This is an untapped industry with unbelievable potential,” says Toombs.

— Heather Wiedenhoft

Heather Wiedenhoft is a Research Scientist at Washington State University.

Advertisement

- Wyoming shrimp farm benefits from oil industry’s abandoned water wells

- Marine Harvest invests $35 million in ‘fish spa’